Reflecting on a year of Gamedev in Zig

One year ago, I started programming a puzzle game from scratch in Zig. While it’s too early to announce the game (more on this later in the year), I want to share some of the insights I’ve gained about gamedev in Zig so far.

I’m writing this because I’ve seen a lot of takes on Zig from folks who’ve spent a relatively short amount of time with the language (e.g. for Advent of Code), but relatively few from people who’ve used the language for more than a year.

While the insights and examples below ultimately came out of gamedev, I’ve tried to focus on aspects of the language and ecosystem that are broad enough to be applicable to people outside of gamedev too; hopefully they’ll be useful to anyone considering attempting a large project in Zig in the near future.

1. The Zig Discord is incredibly helpful with solving elementary AND intermediate-level language problems.

The Zig Discord is a great resource for anyone learning Zig. At any given time, the zig-help forum is awash with questions from beginners like “How do you make for loop in reverse? or “What allocator to use in WASM?” Most get answered within minutes.

Anyone programming a 3D game from scratch, however, will undoubtedly stumble across language problems that lie in higher difficulty classes. I’ve encountered a handful, and was delighted to find that in most cases the Zig Discord not only answered them, but did so within minutes too. Let me illustrate such an example.

During a particular playtesting session, I built my game on a laptop, then copied the binary to a USB. When my friend tried to launch the game on his desktop from the USB, it started but then immediately crashed. We were both running the same operating system, and the game ran as expected on my laptop. What was going on?

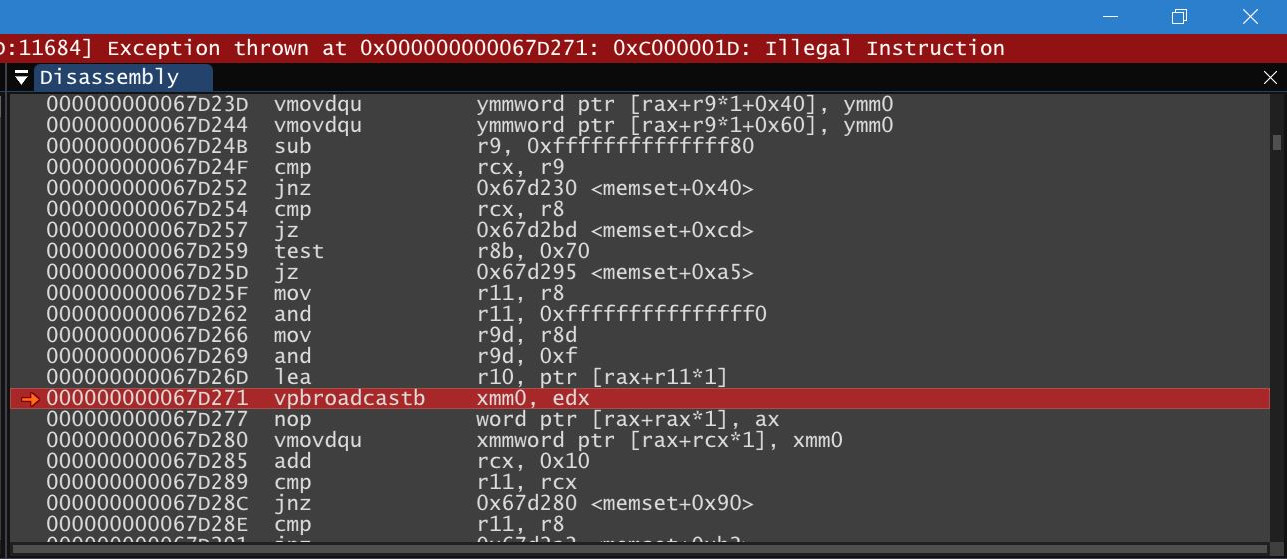

I reduced the problem to the most basic case by creating a “Hello World!” binary in Zig. When this also crashed on my friend’s desktop, I ran it through a portable debugger (RemedyDB). I was shocked to find that the binary contained an unrecognized instruction.

Huh?! I hadn’t built the binary in an odd way — I had used a standard zig build --Doptimize=ReleaseFast command.

I turned to the Zig Discord, and soon the problem was identified and solved: when Zig is compiled with optimizations turned on, by default it uses the best microarchitecture available.

Our CPUs both expected x86-64 instructions, but my laptop expected x86-64-v4 while my friend’s desktop expected x86-64-v2. My CPU knew how to handle the vpbroadcast instruction; my friend’s CPU did not.

After compiling the game with the flag -Dcpu=baseline, the binary contained only x86-64-v1 instructions, allowing my friend to play the game.

If it wasn’t for the Zig Discord, it probably would have taken me days to figure out a fix. But the number of folks on the Discord with expertise on compiler internals meant it was solved in under a quarter of an hour.

2. Zig has good builtin support for vectors, but not for matrices.

Vectors are obviously an essential part of any 2D and 3D game engine. Zig has builtin support for them, meaning that many operators support vector types, and will compile to use SIMD instructions where possible.

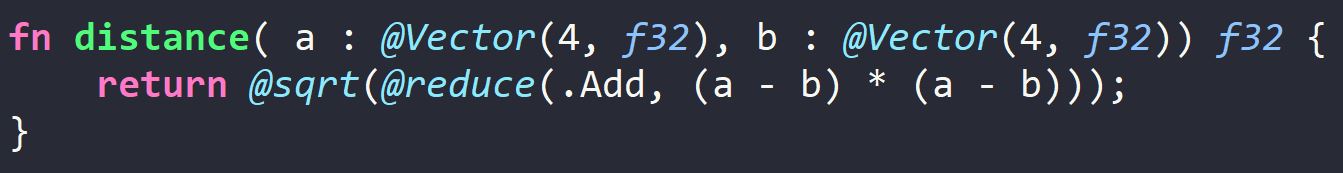

For example, consider calculating the Euclidean distance between two four-dimensional vectors. In Zig, this is as simple as defining the following function:

When compiled, even in debug mode, Zig knows that this operation can be computed with a couple of SIMD instructions — there is no need to subtract and multiply each of the vector’s components individually when a single vsubps and vmulps instruction is enough:

(The instructions for the @reduce() step are a bit inefficient, but again, this is assembly from debug mode.)

I would love to report that Zig has similar builtin support for matrices, but this not the case (yet). If you want even basic linear algebra support, you’ll have to write a bespoke library yourself, or use an existing C library.

This isn’t a dealbreaker for me since I’m writing the engine for my game anyway, but I know some folks would want official matrix support in some capacity before beginning a similar project.

3. The Zig build system is a breath of fresh air compared to CMake, Ninja, Meson, etc.

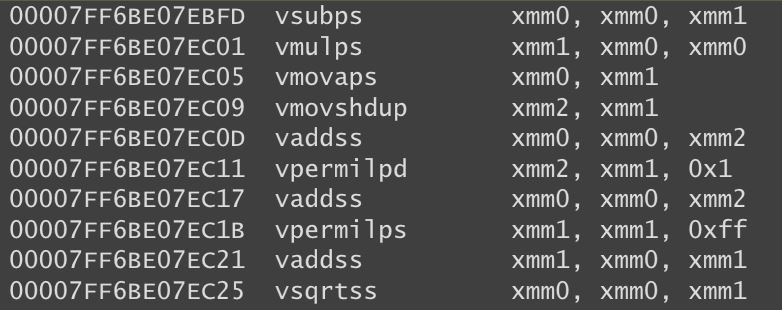

Last year I took a foray into high-performance computing. I was reading the source of the GMP arithmetic library, widely used throughout computational scientific research, and discovered the following in its build system:

You don’t need to have experience with build systems to recognize that this is a disaster. (Note: screenshot taken from the current GMP release, 6.3.0.)

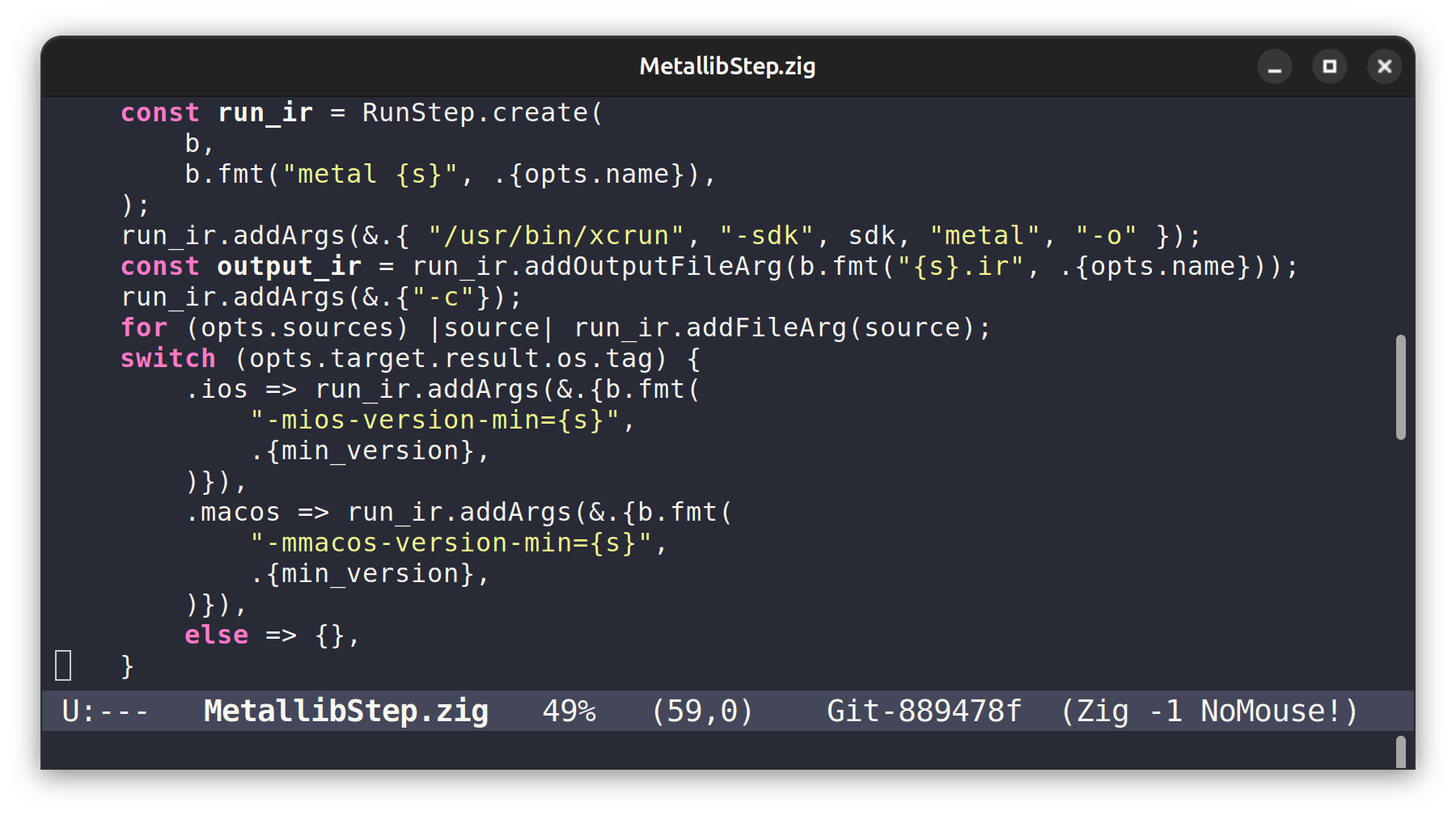

By contrast, here’s a portion of a build file for Ghostty, the latest open-source project from Mitchell Hashimoto, written in Zig. The difference is as clear as night and day:

Okay, I admit to cherry-picking here — I chose a file generated by automake — and I don’t mean to single out GMP in particular. But I think that these examples are representative of the difference between other build systems, and Zig’s.

For me, using the Zig build system for my game has been a better experience than what I’ve had with all other build systems.

I won’t lie, learning the Zig build system is not easy — it often gives me headaches. But CMake is a subarachnoid hemorrhage by comparison. Compiling a moderately complicated C/C++ project should not require knowledge of arcane scripting languages.

In contrast to most build systems, Zig build files are themselves Zig programs. Since the source code of the build system is part of the standard library, you can debug it like any Zig program (e.g. you can insert your own print statements into the build system library — as I have occasionally done).

4. There are incomplete parts of the standard library (and this is mostly okay).

Last year, I wanted to create an icon in my game that consisted of cube spinning on a vertical axis going through two opposite corners, like so:

You can rotate a cube from its canonical orientation (centered at the origin, edges parallel to the XYZ axes) into this configuration with two consecutive simple rotations:

- A rotation by π / 4 around the X-axis, making the “top” of the cube an edge.

- Rotation by θ along the other horizontal axis.

Exercise: what is θ? (Hint: it is NOT equal to π / 4.)

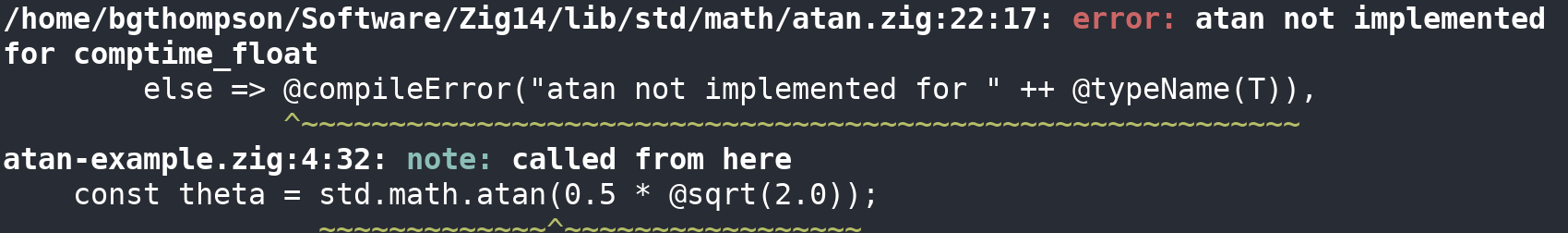

When I tried compiling my game with a calculation of θ, however, I got the following error:

Moments like these are not common, but remind me why the compiler I’m using — 0.14.0 — has a zero at the front.

While this specific instance was slightly annoying, it wasn’t a big deal: I just baked-in the angle. But I think it’s important to know that while working on a big Zig project today, problems due to the standard library being incomplete like this will surface and you’ll need to work around them.

5. The compiler regularly changes in big, exciting, and breaking ways.

While working on my game, I’ve gone through several Zig compiler releases. Each time, something failed when I tried to build the game with the new compiler. Either the build system itself had been updated, or the language itself had breaking changes, or both.

But in each case I was able to get the game compiling again within two hours. Since there are only two major releases a year, it’s not that much of a hassle.

In return, I’ve experienced a plethora of positive changes to the language and toolchain.

For one, compile times have become faster in each release. Others have noted increases in application performance too: Mitchell Hashimoto reported that the scrolling benchmarks on Ghostty got 3-5% faster after transitioning from Zig 0.13.0 to 0.14.0 (but cautioned that this may be noise).

I should note that a big reduction in debug compile times is just around the corner too. The Zig team have nearly eliminated a dependency on LLVM to produce debug builds on x86-Linux. I’ve used the new x86 backend to compile some basic programs, and it leaves the LLVM backend in the dust. While the new backend doesn’t currently compile my game because of my extensive use of vectors — I get errors such as TODO implement airReduce for @Vector(3, f32) — I fully expect that once complete, the reduction in compile times will be significant.

Another change has been the --watch compile option (e.g. zig build --watch). This keeps the compiler in a permanently “on” state, watching source files for changes. As soon as it detects a change in a file, it attempts another compile.

Having the compiler automatically and quickly find the next error in my code after I save an edit without having to interface with an LSP saves me a bunch of time and is satisfying. When combined with incremental compilation (another feature coming soon), the latency between saving an edit and a compile attempt finishing may end up being less time than it takes to click one’s fingers.

I could go on, but I’ll leave here for now. Overall, I’ve had an great time building a game in Zig so far. I don’t have many complaints. Since the language, toolchain, and standard library are still under active development, many of the complaints I do have will likely be addressed in upcoming releases. I’m excited to continue to work on the game in Zig, and for the upcoming Zig releases.